Fungi: Science, Materiality, and a Sustainable Future

Fungi have evolved from discreet organisms into one of the most promising fields for sustainable innovation. Their ability to generate alternative proteins and biomaterials comparable to leather has captured the attention of scientists and industries such as food and fashion. Yet this universe remains surprisingly unfamiliar to the general public, despite the growing body of scientific evidence supporting its potential.

in the food sector, multiple studies have shown that mycelium—the filamentous network that forms most of the fungal organism—can be cultivated as a high‑quality protein source. Research published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry demonstrated that species such as Pleurotus djamor can grow on vegetable residues and produce biomass rich in protein, fiber, and essential amino acids. This type of fungal protein has even shown higher sensory acceptance than traditional plant‑based alternatives, suggesting significant potential for the food industry. Additionally, mushrooms such as shiitake, maitake, and reishi have been extensively studied for their protein content and bioactive compounds, as documented in Food Chemistry and the International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms, where their immunomodulating and antioxidant beta‑glucans are highlighted.

The sustainability of mushroom cultivation is also well established. Organizations such as the FAO

ave noted that fungi require minimal water and can be grown on agricultural waste, significantly reducing pressure on food systems. Complementing this, analyses by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation,

Ellen MacArthur Foundation emphasize mycelium as a resource aligned with circular‑economy principles due to its ability to transform organic waste into valuable biomass.

In the fashion industry, mycelium is quietly leading a material revolution. A study published in Life evaluated five fungal species—including Cubamyces flavidus, Lentinus squarrosulus, and Ganoderma gibbosum—and demonstrated that they can produce dense, flexible sheets with properties comparable to materials used in leather goods. Although these biomaterials present technical challenges, such as shrinkage during drying, the research confirms their viability as substitutes for animal and synthetic leather. This scientific work aligns with industrial developments from companies like MycoWorks and Bolt Threads, whose materials Reishi™ and Mylo™ have been documented in technical literature and design analyses published by Springer, describing how mycelium can be cultivated, pressed, and stabilized to create textile‑ready surfaces.

International research further supports this progress. Institutions such as Vrije Universiteit Brussel, University of Utrecht y Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have demonstrated that mycelium can form continuous structures that, after specific treatments, acquire resistance, flexibility, and textures comparable to leather [8]. These findings align with studies on fungal biocomposites published by Springer Nature, which highlight the role of design and biofabrication in creating mycelium‑based materials for textile, architectural, and product applications.

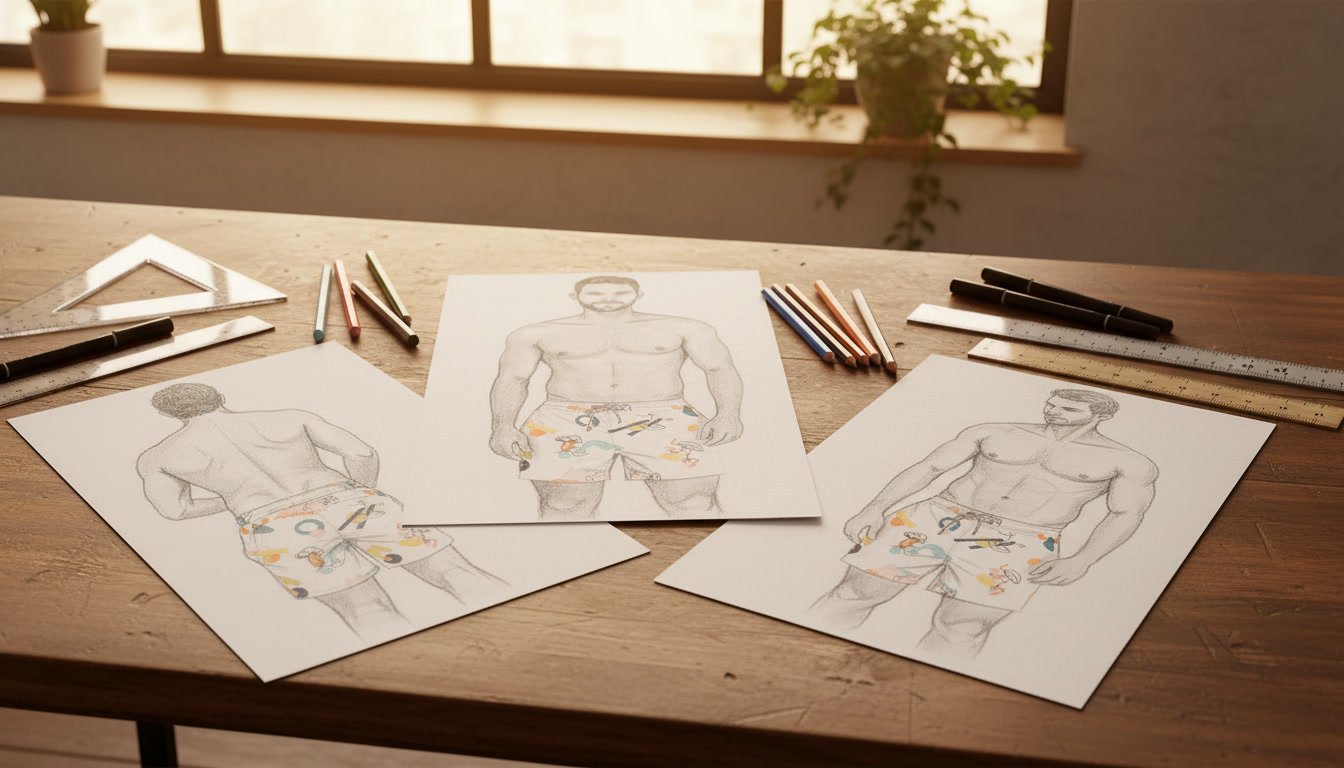

All this scientific evidence—revealing fungi as organisms capable of transforming waste into resources, generating proteins, and becoming materials with their own identity—inspired the prints of Bénieller’s Happy Mushrooms and Life in Colors references. Both designs reinterpret the fungal universe visually: not through literal representation, but through the vital energy, chromatic diversity, and biological intelligence embedded in mycelium. Science becomes visual narrative, and the laboratory becomes a symbolic landscape that shapes the aesthetic of the collection.

Despite these advances, the use of fungi in fashion remains an emerging and little‑known field. Most consumers—and even many industry professionals—are unaware of which species are used, how these biomaterials are cultivated, or what environmental impact they have. This gap between science, industry, and material culture explains why mycelium, despite its potential, has not yet achieved widespread adoption.

The intersection of food and fashion reveals a clear pattern: fungi are extraordinarily versatile organisms, capable of transforming waste into resources and generating nutritious or textile materials with minimal environmental impact. Their natural alignment with circular‑economy principles positions them as one of the most promising pillars for a sustainable future. As science advances and brands adopt fungal biomaterials, fungi may become a central resource for industries seeking to reduce their dependence on non‑renewable materials.